Navigating Workplace Tensions: The Five Conflict Management Styles

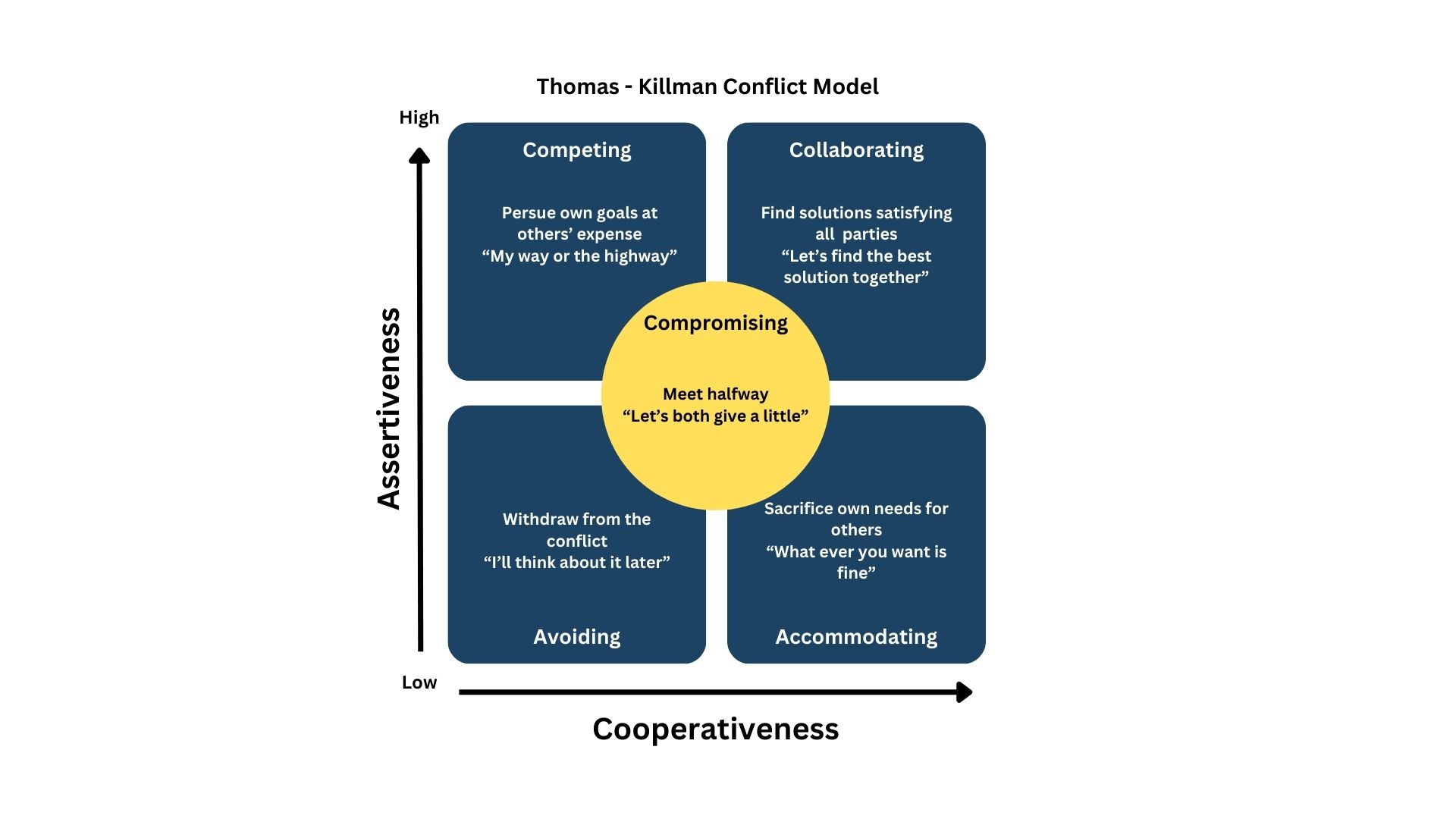

In the fast-paced world of modern business, conflict is inevitable. From minor disagreements over project timelines to major disputes about strategic direction, how leaders handle these tensions can make or break team dynamics and organizational success. The Thomas-Kilmann model identifies five distinct conflict management styles: avoiding, competing, accommodating, compromising, and collaborating. But how do these play out in real-world scenarios? Let’s follow the journey of Sarah Chen, a newly appointed director of product development at Horizon Technologies, as she navigates a challenging quarter using each of these approaches.

The Challenge Begins

Sarah stepped into her new role with enthusiasm and big ideas. With fifteen years of industry experience and a reputation for innovation, she was eager to make her mark on Horizon’s flagship product line. But just three weeks in, she faced her first major challenge: the engineering team, led by veteran manager Marcus, was pushing back against her proposed timeline for the new product release.

“We need at least three more months,” Marcus insisted during a tense meeting. “Your schedule is simply unrealistic given our current resources.”

Several senior team members nodded in agreement, while the marketing department representatives looked dismayed. They had already begun planning the product launch campaign based on the original timeline Sarah had proposed.

How Sarah handled this conflict would set the tone for her leadership. Let’s explore the different conflict management styles and how each of them might play out in this scenario, and what lessons we can learn from each approach.

Style 1: Avoiding – The Path of Least Resistance

In our first scenario, Sarah chooses avoidance. After the challenging meeting, she decides to sidestep the conflict entirely.

“Let’s table this discussion for now and move on to other agenda items,” she says, quickly changing the subject. “We’ll circle back to the timeline issue when we have more data.”

Over the following weeks, Sarah continues to delay addressing the disagreement. She reschedules meetings where the topic might arise and redirects conversations when team members bring up timeline concerns. She hopes that perhaps the engineering team will find a way to speed up their process, or that the issue will somehow resolve itself.

The Outcome: Six weeks later, the conflict erupts again, but now with greater intensity. The engineering team has continued working at their original pace, assuming their timeline would be honored. Meanwhile, marketing has proceeded with launch preparations according to Sarah’s initial schedule. The project is now in serious jeopardy, team members are frustrated, and Sarah’s credibility has been damaged.

When Avoiding Works: While avoidance failed Sarah in this scenario, this approach can be appropriate in certain situations:

- When the issue is trivial compared to more important matters requiring attention

- When tensions are high and a cooling-off period is needed

- When more information is needed before addressing the problem

- When you have no power to effect change in the situation

When Avoiding Fails: Avoidance typically backfires when:

- The issue is important and won’t resolve itself

- Delayed decisions will cause greater problems

- The conflict involves core responsibilities that can’t be delegated or ignored

- Trust and credibility are at stake

Style 2: Competing – Standing Firm

In our second scenario, Sarah takes a competitive approach to the conflict.

“I understand your concerns,” she tells Marcus firmly, “but as the new product director, I’ve been brought in specifically to accelerate our development cycle. The timeline stays as is. I need your team to find a way to make it work.”

She follows up with an email to the entire department reiterating the deadline and her expectations. When Marcus attempts to raise his concerns again, Sarah reminds him of the company’s goals to outpace competitors and implies that his resistance appears as an unwillingness to embrace necessary change.

The Outcome: The engineering team reluctantly commits to the accelerated timeline but morale suffers. Team members work overtime, cutting corners where possible. The product launches on schedule, but with several unresolved bugs that the exhausted engineering team couldn’t address in time. Customer complaints begin rolling in, and Marcus’s “I told you so” attitude creates a lingering rift between engineering and product development.

When Competing Works: The competing style can be effective:

- In genuine emergencies requiring quick, decisive action

- When implementing necessary but unpopular changes

- When protecting yourself from people who take advantage of non-competitive behavior

- When the relationship is less important than the outcome

When Competing Fails: This approach often creates problems when:

- Cooperation from others is needed for successful implementation

- Long-term relationships and team cohesion are important

- The other party has equal or greater power

- The issue requires integration of multiple perspectives

Style 3: Accommodating – Yielding to Others

In our third scenario, Sarah chooses to accommodate the engineering team’s concerns completely.

“I value your expertise, Marcus,” she says. “If you believe we need three more months for quality assurance, then we’ll adjust to your timeline.”

She informs the marketing team that they’ll need to postpone their launch plans and accepts full responsibility for the schedule change with upper management, despite knowing it might reflect poorly on her early performance.

The Outcome: The engineering team appreciates Sarah’s respect for their professional judgment, and Marcus becomes a supportive ally. The product launches three months later than originally planned with excellent quality and minimal bugs. However, Horizon misses a key market opportunity as a competitor releases a similar product during the delay. Upper management questions whether Sarah has the assertiveness needed for her role.

When Accommodating Works: Accommodation can be an appropriate strategy:

- When you discover you’re wrong or the issue is more important to others

- When preserving harmony is especially important

- When building social capital for future issues that matter more to you

- When minimizing losses when you’re in a position of weakness

When Accommodating Fails: This approach can be problematic when:

- The issue is too important to concede

- Others may take advantage of such behavior

- Your credibility and influence might be diminished

- The best solution requires integration of multiple viewpoints

Style 4: Compromising – Meeting Halfway

In our fourth scenario, Sarah opts for compromise.

“I hear your concerns about quality and resources,” she tells Marcus. “What if we split the difference? Instead of three months extra, we push the deadline by six weeks, and I’ll see if we can get approval for additional temporary resources to help meet this middle ground.”

After some negotiation, both departments agree to the adjusted timeline. Marketing scales back some launch activities, and engineering agrees to prioritize certain features while deferring others to a point release.

The Outcome: Neither team gets exactly what they wanted, but work proceeds with a shared sense of having been heard. The product launches six weeks later than Sarah’s original plan but earlier than engineering had requested. Some minor issues still emerge, but they’re manageable. Both teams feel the solution was fair, if not ideal.

When Compromising Works: Compromise is particularly effective:

- When parties have roughly equal power and strongly held views

- When time constraints demand an expedient solution

- When goals are moderately important but not worth a more assertive approach

- When temporary solutions are needed for complex issues

When Compromising Fails: This middle-ground approach falls short when:

- One side makes concessions while the other doesn’t follow through

- Important principles or values are at stake

- Creative, integrative solutions could produce better outcomes

- The compromise misses addressing underlying issues

Style 5: Collaborating – Finding the Win-Win

In our final scenario, Sarah takes a collaborative approach to resolving the conflict.

“I want to understand exactly what obstacles you’re seeing with the timeline,” she says to Marcus. Instead of debating in the large meeting, she schedules a working session with key stakeholders from both engineering and marketing.

During this session, she encourages open discussion about specific concerns. “What resources would you need to meet a more aggressive timeline? Which features are causing the biggest delays? Are there any alternative approaches we haven’t considered?”

Through this in-depth exploration, the team discovers that certain features causing significant development delays are actually lower priorities for customers than marketing had assumed. They also identify opportunities to bring in specialized contractors for specific components rather than overburdening the internal team.

The Outcome: The group develops a revised plan that launches the product’s core functionality on Sarah’s original timeline, with a clearly communicated roadmap for additional features to follow in regular updates. Engineering secures the additional resources they need, while marketing gets their timely launch with a compelling story about continuous innovation. Upper management is impressed with Sarah’s leadership in finding a creative solution, and team cohesion strengthens through the collaborative process.

When Collaborating Works: Collaboration is ideal when:

- The issues and relationships are both highly important

- Creative integration of different perspectives could yield better solutions

- Buy-in from all parties is critical for implementation

- There’s sufficient time to work through complex issues thoroughly

When Collaborating Fails: Even this generally optimal approach has limitations:

- When time is too limited for thorough exploration

- When issues are trivial and don’t warrant the investment of time

- When parties lack the skills or facilitation to engage productively

- When fundamental values or objectives are truly incompatible

The Balanced Approach

As Sarah’s hypothetical journey shows, no single conflict management style works best in all situations. The most effective leaders develop flexibility, employing different approaches depending on the specific circumstances they face.

Over time, Sarah learned to assess each conflict situation by asking herself key questions:

- How important is this issue to me and to others involved?

- How crucial is this particular relationship for long-term success?

- What power dynamics are at play?

- What time constraints do we face?

- What might be hidden beneath the surface of the stated positions?

By developing this situational awareness, she became known not just for her technical expertise, but for her emotional intelligence and conflict resolution skills.

Your Conflict Management Styles Journey

We all have natural preferences among the five conflict management styles. Some of us instinctively avoid confrontation, while others may typically compete or compromise. These tendencies often stem from our personalities, cultural backgrounds, and early experiences with conflict.

The key to growth isn’t abandoning your natural style but expanding your repertoire so you can choose the most appropriate approach for each unique situation. With practice and self-awareness, you can develop the flexibility that distinguishes truly exceptional leaders.

Next time you face workplace conflict, try stepping back to assess the situation before responding. Consider which style—avoiding, competing, accommodating, compromising, or collaborating—might serve both the issue and relationships best in this particular context. Over time, this reflective practice will become second nature, transforming you into the kind of leader who turns inevitable conflicts into opportunities for innovation, growth, and stronger team bonds.

Remember: conflict itself isn’t the problem. It’s how we manage it that determines whether it becomes a destructive force or a catalyst for positive change.

If you want to explore how Sun Dog Consulting can help you with conflict management styles, get in touch with us and book a call.

More From This Category

Difficult Conversations at Work: A Script for Leaders

Master difficult conversations at work with proven scripts and frameworks. Turn challenging discussions into opportunities for growth and trust

Conflict: A Necessary Catalyst for Growth

Conflict: A Necessary Catalyst for Growth While it may seem counterintuitive, conflict can actually be a positive and necessary force in our lives. When people have differing beliefs, opinions or needs, it's natural for some level of conflict to arise. Rather than...